The field of metaethics is broadly concerned with the following questions: are there any true moral facts? And if so, how can we come to know them?

As an example of what this would mean: take natural-rights libertarianism, as espoused by Robert Nozick, Murray Rothbard, and legions of spotty teenagers. According to this theory, there exist certain facts along the lines of the following:

(a) The copy of Anarchy, State, and Utopia upstairs is my property.

(b) For any entity X, if X is my property then others ought not to interfere with my usage of X unless my usage of X interferes with their usage of an entity Y which is their property.

Of course, a lot of attention in this kind of theory will be devoted to exactly what it means to say that an entity is someone's property. A standard response made by a non-libertarian philosopher would be to observe that the notion of property is entirely socially constructed. To bring out the difference between socially-constructed and non-socially-constructed features of things, compare the properties of belonging to a person and of being less dense than water. Whether something belongs to me or my neighbour is determined entirely by the beliefs of society: if everyone believes the copy of ASU upstairs belongs to my neighbour, it's not that everyone is wrong - it's that the book actually is my neighbours, and I will be obliged to return it to him at the next opportunity. If something is less dense than water, however, it matters not one jot what any of us believes - it will float, and all the assertions in the world will not change that.

Since property is socially constructed, then, perhaps we ought to construct it strategically so that it operates to the greatest advantage of all. Thus we might decide to agree that notions such as taxation are baked into the very notion of property: taxation is not theft, but simply the proper functioning of the property system. (There's a more ambitious version of this argument which holds that no property would exist without a state and so submission to the state in general is part of what it means to own property, but this is silly because (a) property has existed throughout history without the existence of states and (b) even if that were not the case, it's not at all clear how the move from an is to an ought is supposed to be occurring here).

One thing that would support natural rights libertarianism, then, would be if facts about property somehow turned out not to be socially constructed but to be intrinsic features of the world in the same way as density. It turns out that there is a well-known fictional universe in which this is the case: the Harry Potter novels, in which a key reveal towards the end of the last book is that the Elder Wand, a weapon of deadly power, never truly recognised Voldemort as its possessor - despite him having wielded it for much of the last book, ever since he ransacked the tomb of Dumbledore, a previous owner of the Wand. Instead, the wand recognised first Draco Malfoy and then Harry Potter as its true owner, despite neither of them having prior to this point even touched the wand. In the Harry Potter universe, ownership is not a social construct but a real and tangible feature of the universe - and so it may well be impossible, even if desirable, to move to a more socially beneficial meaning of the notion of "property".

Libertarians should not rejoice too quickly, however: the way the wand passes between owners almost always involves violation of the Non-Aggression Principle. Grindelwald stole it from Gregorovitch, Dumbledore kept it after defeating Grindelwald, Malfoy ambushed and disarmed Dumbledore, Harry burgled and overpowered Malfoy. While there are substantial facts about property, which stand in addition to the facts which are known through science and empiricism, they are surely different from the facts which libertarians would have us believe. Perhaps not entirely different - wands aside, most objects seem to behave much as they do in the actual universe with regard to owners - but not the same either.

As a final aside, it is interesting to note that this universe also contains one of the more notable examples of a society with markedly different but non-utopian rules concerning property. I refer, of course, to the goblins, who believe all objects to truly belong to their makers: one cannot purchase an object, only rent it for life. To pass on to one's heirs something that one did not produce oneself is regarded by goblins as theft. Unless the original maker of the Elder Wand is still alive (and according to tradition, the wand was in fact made by Death Himself), this theory must surely remain live as a possible metaethical truth about property in the Harry Potter universe.

Showing posts with label Libertarianism. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Libertarianism. Show all posts

Tuesday, 22 August 2017

Sunday, 14 May 2017

How Have My Political Views Changed Over Time?

I sometimes wonder if I'm too locked into my political ideology. I have been a libertarian of some sort basically as long as I've known what the word means, i.e. about seven years. However, in that time my views on various individual issues have changed; hopefully this means that the fear in my first sentence is not too accurate?

In any case, here is a set of notes I came up with when trying to work out how my views have changed. The four big driving forces between the changes have been:

-I became much less confident in the possibility of "moral truth", which (a) reduced my commitment to making everything fully consistent and (b) made me more sanguine about advancing political positions on aesthetic grounds. (This is quite possibly a negative development; that said, it made it easier to be honest about my real motivations for some policies, e.g. monarchism).

-aged 18, I was a committed Christian and so if I were to hold a belief about politics, either it had to be consistent with Biblical teachings or I had to twist my understanding of the Bible to fit my political leanings. (I remember being very upset when I read Exodus 3:22, which seemed like a blatant endorsement of theft). Between October 2013 and April 2014, I became convinced that Christianity is false.

-in Sixth Form and the first year of undergrad, I knew no other libertarians and the closest I could find to people who agreed with me were a couple of socially-liberal Tories; during the second-year of undergrad I got to know Sam Dumitriu, who eventually got me to start using Twitter, with the result that I quickly fell in with the #MCx crowd. We are all influenced by the people we talk to, partly because of honest intellectual influence but mostly because of a desire to fit in and look cool; hence my move to "neoliberalism" over "libertarianism".

-partly due to my loss of faith in deontological libertarian moral realism and partly due to people on Twitter - most obviously Sam Bowman and Ben Southwood - I became much more utilitarian. It's hard to date this exactly, but I particularly remember one afternoon of summer 2016 spent walking in County Kerry with my dad, when I concluded that either one took the Enlightenment seriously or one didn't' If one didn't, then what resulted was a tribalist, emotivist politics that was honest, if barbaric. If one took the Enlightenment seriously, then either one concluded that other people matter - in which case, why not go all the way to utilitarianism? - or only oneself matters, in which case ethical egoism results. Concepts like citizenship are attempts to maintain the visceral emotional appeal of pre-enlightenment politics in a post-Enlightenment context, but I think this attempt is ultimately dishonest. Emotional appeal ought to be abstracted as far as possible (which is not the same as removed!) from a political system based on reason. I've moved away from this somewhat since, but remain basically utilitarian.

With that overly long explanation out of the way, a list of fifteen ways in which my views have changed (still in note format but with some explanatory links added, I'm not going to tidy this up):

-used to consider anarchism to be the moral ideal towards which we should aim. Circa 2014 concluded that it was probably both viable and better than status quo, but minarchism to be preferred as a way of controlling negative externalities. Nowadays (since early 2017) suspect it may be unstable due to people's tribal instincts - though still would like to see it tried!

Given the supposition of a government:

1-used to advocate "liquid democracy". Now heavily opposed to anything approaching direct democracy, and would advocate for UK and other major liberal powers to be less democratic on the margin. Had a period of extreme scepticism of democracy due to Jason Brennan (circa early 2013-late 2016 or early 2017); now think it has important instrumental-expressive purposes in maintaining public order.

2-used to be uneasy about redistribution in principle, but would tolerate sufficientarianism. Now at peace with the principle of redistribution, though heavily concerned about *how* it is implemented. Partly due to Joseph Heath (ctrl-f "risk-pooling"), partly due to becoming more neoliberal/utilitarian, which is probably more due to the people I talk with than due to any particular argument. (Took a long time, but roughly late 2013-mid 2016)

3-used to be heavily opposed to military interventions. Now cautiously in favour, largely due to the influence of Mugwump. (still in flux)

4-used to be heavily concerned about tax rates. Still think they matter, but no longer consider them the highest priority. Always thought *how* we taxed matters, though have a more sophisticated understanding of taxation theory than I did back then. Used to advocate negative income tax; now prefer progressive consumption tax.

5-realised free trade is about much more than tariffs and quotas - free trade agreements serve a genuinely valuable purpose. Relatedly, was eurosceptic; switched to being pro-EU around late 2014, as a result of debate preceding the referendum became vastly more pro-EU. (Possibly also related to change in self-image due to living in Hungary for two years).

6-was unconcerned about fertility. Now consider it a top priority, mostly due to Nancy Folbre though partly due to combination of Parfit/Cowen on discounting the future with my own work opposing antinatalism. (early 2015-present)

7-used to assume that Austrian goldbuggery was sensible. (How embarrassing!) Have given up having strongly held views on monetary policy, though Scott Sumner is fairly persuasive. (change around early 2013 - mid 2015?)

8-as natural-rights libertarian, assumed there was a definite answer to whether or not intellectual property was valid, leaned towards not. Nowadays take a much more utilitarian view, thinking that in purely instrumental terms there should probably be some but less than we currently have.

9-was pro-open-borders. Now merely think we should have open borders for citizens of other liberal democracies, and higher but not unlimited immigration from less liberal countries. Didn't care about integration, seeing it as a service provided by host country to people who should be quite happy to reap the benefits of moving to a richer country; now see integration as an act of self-defence. (2016?)

10-thought we should tolerate more terrorism. Still think it's greatly overrated as a threat, but think that (a) preventing people from overreacting is intractable, and (b) costs of anti-terrorism much smaller than I thought back then.

11-struggled to find a reason to be monarchist while still being anarchist. Now I'm (a) less of a moral realist so happier to advocate political institutions on aesthetic grounds, (b) equipped with evidence that Habsburgs were good for Mitteleuropa.

12-was heavily opposed to existence of national debt. Now think morality of national debt dependent upon other institutions, in particular with how much we do to encourage fertility. (2015-early 2017, especially more recently with my work opposing anti-natalism: I came to think that we ought to subsidise procreation, but it seemed fair that the people benefitting by being born ought to bear the cost of subsidies)

13-felt reasonably comfortable with Conservative Party. Also thought UKIP were alright. Think Tories and Labour worse than they were back then, probably happier with Lib Dems than I was. (this probably more due to changes in the parties than changes in my own views, however)

14-thought strong governments (and consequently FPTP) were hugely important. Don't think I had any good reason for this belief. Now hold no strong opinions on this beyond "it depends". (Don't know when this changed, but probably not before 2011 AV+ referendum)

15-now advocate returning the Elgin Marbles. Felt awkward about this in much the same way as the monarchy insofar as I thought about it at all; this Ed West tweet convinced me that they ought, so long as Greece can look after them (which it admittedly might not be able to given the current economic situation), that they ought to be returned ASAP. (This is perhaps the only change in my views which happened in a single moment rather than over time).

In any case, here is a set of notes I came up with when trying to work out how my views have changed. The four big driving forces between the changes have been:

-I became much less confident in the possibility of "moral truth", which (a) reduced my commitment to making everything fully consistent and (b) made me more sanguine about advancing political positions on aesthetic grounds. (This is quite possibly a negative development; that said, it made it easier to be honest about my real motivations for some policies, e.g. monarchism).

-aged 18, I was a committed Christian and so if I were to hold a belief about politics, either it had to be consistent with Biblical teachings or I had to twist my understanding of the Bible to fit my political leanings. (I remember being very upset when I read Exodus 3:22, which seemed like a blatant endorsement of theft). Between October 2013 and April 2014, I became convinced that Christianity is false.

-in Sixth Form and the first year of undergrad, I knew no other libertarians and the closest I could find to people who agreed with me were a couple of socially-liberal Tories; during the second-year of undergrad I got to know Sam Dumitriu, who eventually got me to start using Twitter, with the result that I quickly fell in with the #MCx crowd. We are all influenced by the people we talk to, partly because of honest intellectual influence but mostly because of a desire to fit in and look cool; hence my move to "neoliberalism" over "libertarianism".

-partly due to my loss of faith in deontological libertarian moral realism and partly due to people on Twitter - most obviously Sam Bowman and Ben Southwood - I became much more utilitarian. It's hard to date this exactly, but I particularly remember one afternoon of summer 2016 spent walking in County Kerry with my dad, when I concluded that either one took the Enlightenment seriously or one didn't' If one didn't, then what resulted was a tribalist, emotivist politics that was honest, if barbaric. If one took the Enlightenment seriously, then either one concluded that other people matter - in which case, why not go all the way to utilitarianism? - or only oneself matters, in which case ethical egoism results. Concepts like citizenship are attempts to maintain the visceral emotional appeal of pre-enlightenment politics in a post-Enlightenment context, but I think this attempt is ultimately dishonest. Emotional appeal ought to be abstracted as far as possible (which is not the same as removed!) from a political system based on reason. I've moved away from this somewhat since, but remain basically utilitarian.

With that overly long explanation out of the way, a list of fifteen ways in which my views have changed (still in note format but with some explanatory links added, I'm not going to tidy this up):

-used to consider anarchism to be the moral ideal towards which we should aim. Circa 2014 concluded that it was probably both viable and better than status quo, but minarchism to be preferred as a way of controlling negative externalities. Nowadays (since early 2017) suspect it may be unstable due to people's tribal instincts - though still would like to see it tried!

Given the supposition of a government:

1-used to advocate "liquid democracy". Now heavily opposed to anything approaching direct democracy, and would advocate for UK and other major liberal powers to be less democratic on the margin. Had a period of extreme scepticism of democracy due to Jason Brennan (circa early 2013-late 2016 or early 2017); now think it has important instrumental-expressive purposes in maintaining public order.

2-used to be uneasy about redistribution in principle, but would tolerate sufficientarianism. Now at peace with the principle of redistribution, though heavily concerned about *how* it is implemented. Partly due to Joseph Heath (ctrl-f "risk-pooling"), partly due to becoming more neoliberal/utilitarian, which is probably more due to the people I talk with than due to any particular argument. (Took a long time, but roughly late 2013-mid 2016)

3-used to be heavily opposed to military interventions. Now cautiously in favour, largely due to the influence of Mugwump. (still in flux)

4-used to be heavily concerned about tax rates. Still think they matter, but no longer consider them the highest priority. Always thought *how* we taxed matters, though have a more sophisticated understanding of taxation theory than I did back then. Used to advocate negative income tax; now prefer progressive consumption tax.

5-realised free trade is about much more than tariffs and quotas - free trade agreements serve a genuinely valuable purpose. Relatedly, was eurosceptic; switched to being pro-EU around late 2014, as a result of debate preceding the referendum became vastly more pro-EU. (Possibly also related to change in self-image due to living in Hungary for two years).

6-was unconcerned about fertility. Now consider it a top priority, mostly due to Nancy Folbre though partly due to combination of Parfit/Cowen on discounting the future with my own work opposing antinatalism. (early 2015-present)

7-used to assume that Austrian goldbuggery was sensible. (How embarrassing!) Have given up having strongly held views on monetary policy, though Scott Sumner is fairly persuasive. (change around early 2013 - mid 2015?)

8-as natural-rights libertarian, assumed there was a definite answer to whether or not intellectual property was valid, leaned towards not. Nowadays take a much more utilitarian view, thinking that in purely instrumental terms there should probably be some but less than we currently have.

9-was pro-open-borders. Now merely think we should have open borders for citizens of other liberal democracies, and higher but not unlimited immigration from less liberal countries. Didn't care about integration, seeing it as a service provided by host country to people who should be quite happy to reap the benefits of moving to a richer country; now see integration as an act of self-defence. (2016?)

10-thought we should tolerate more terrorism. Still think it's greatly overrated as a threat, but think that (a) preventing people from overreacting is intractable, and (b) costs of anti-terrorism much smaller than I thought back then.

11-struggled to find a reason to be monarchist while still being anarchist. Now I'm (a) less of a moral realist so happier to advocate political institutions on aesthetic grounds, (b) equipped with evidence that Habsburgs were good for Mitteleuropa.

12-was heavily opposed to existence of national debt. Now think morality of national debt dependent upon other institutions, in particular with how much we do to encourage fertility. (2015-early 2017, especially more recently with my work opposing anti-natalism: I came to think that we ought to subsidise procreation, but it seemed fair that the people benefitting by being born ought to bear the cost of subsidies)

13-felt reasonably comfortable with Conservative Party. Also thought UKIP were alright. Think Tories and Labour worse than they were back then, probably happier with Lib Dems than I was. (this probably more due to changes in the parties than changes in my own views, however)

14-thought strong governments (and consequently FPTP) were hugely important. Don't think I had any good reason for this belief. Now hold no strong opinions on this beyond "it depends". (Don't know when this changed, but probably not before 2011 AV+ referendum)

15-now advocate returning the Elgin Marbles. Felt awkward about this in much the same way as the monarchy insofar as I thought about it at all; this Ed West tweet convinced me that they ought, so long as Greece can look after them (which it admittedly might not be able to given the current economic situation), that they ought to be returned ASAP. (This is perhaps the only change in my views which happened in a single moment rather than over time).

Monday, 16 January 2017

Preparing the Ground for Tyrants

(See also: How Good Has Obama's Presidency Been?)

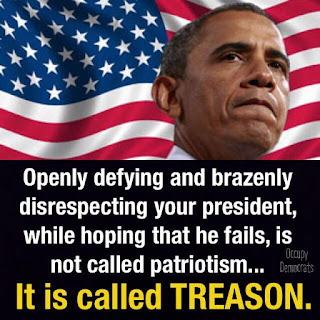

I've seen a couple of libertarians sharing the following graphic on Facebook, commenting upon how much sillier it looks a year later now that Donald Trump is the president-elect:

I'm not certain how useful this video is to my general point, but it feels kind-of related: Obama mocking Mitt Romney during the 2012 debates for viewing Russia as the "number-one threat to America":

These are statements which were made with utter confidence by Democrats at the time, which they now are very eager to repudiate. A related phenomenon has been the inflated stature, under Obama of the executive order. Obama has not, by the standards of modern presidents, issued an especially large number of executive orders: indeed, the last president to issue fewer orders during two terms of presidency was Grover Cleveland in the late 19th century. But by using them to cause the enforcement of laws which Congress had rejected, he has prepared the ground for Trump to do whatever he likes, even beyond the probably Democrat landslides in the 2018 midterm elections.

This brings us to a general point, one made frequently by libertarians and classical liberals: that designers of political systems rarely stop to think what will happen if the wrong people are able to take charge of the country. But this is an inevitable fact of politics: democracies elect bad men, great leaders make poor choices of successor, and revolutionary governments are almost by definition founded by men with a taste for violence. This fact is one that we should take into account when setting up our laws and institutions, and there are three basic responses you can give:

(1) The freedom of action of political actors must be severely curtailed, firstly by checks and balances upon what can be done and secondly by limiting the range of actions which any government is able to do, no matter how internally united it may be.

(2) Yes, there are risks to a powerful executive, but they are risks worth taking. There are bad governments, but (at least in the context of a well-functioning liberal democracy) these are very much the exception.

(3) Embrace the hypocrisy, and accept that ultimately what matters is not the meta-level process of how you determine what governments should be able to do but simply what side you are on, i.e. whether these vast powers are being used for a (by your lights) good cause or a bad one.

The people who talk about this problem explicitly seem almost universally to give answer (1). Answer (3) is closer to most people's unconsidered instincts, and I don't actually think it's obviously wrong. (It's uncomfortable for Democrats to oppose Trump doing the very things they championed under Obama, sure, but is it objectively any easier for him merely because Obama did it? I don't know.) I'd be interested to see a defence of (2), which seems to be the option most applicable to the UK.

I've seen a couple of libertarians sharing the following graphic on Facebook, commenting upon how much sillier it looks a year later now that Donald Trump is the president-elect:

I'm not certain how useful this video is to my general point, but it feels kind-of related: Obama mocking Mitt Romney during the 2012 debates for viewing Russia as the "number-one threat to America":

These are statements which were made with utter confidence by Democrats at the time, which they now are very eager to repudiate. A related phenomenon has been the inflated stature, under Obama of the executive order. Obama has not, by the standards of modern presidents, issued an especially large number of executive orders: indeed, the last president to issue fewer orders during two terms of presidency was Grover Cleveland in the late 19th century. But by using them to cause the enforcement of laws which Congress had rejected, he has prepared the ground for Trump to do whatever he likes, even beyond the probably Democrat landslides in the 2018 midterm elections.

This brings us to a general point, one made frequently by libertarians and classical liberals: that designers of political systems rarely stop to think what will happen if the wrong people are able to take charge of the country. But this is an inevitable fact of politics: democracies elect bad men, great leaders make poor choices of successor, and revolutionary governments are almost by definition founded by men with a taste for violence. This fact is one that we should take into account when setting up our laws and institutions, and there are three basic responses you can give:

(1) The freedom of action of political actors must be severely curtailed, firstly by checks and balances upon what can be done and secondly by limiting the range of actions which any government is able to do, no matter how internally united it may be.

(2) Yes, there are risks to a powerful executive, but they are risks worth taking. There are bad governments, but (at least in the context of a well-functioning liberal democracy) these are very much the exception.

(3) Embrace the hypocrisy, and accept that ultimately what matters is not the meta-level process of how you determine what governments should be able to do but simply what side you are on, i.e. whether these vast powers are being used for a (by your lights) good cause or a bad one.

The people who talk about this problem explicitly seem almost universally to give answer (1). Answer (3) is closer to most people's unconsidered instincts, and I don't actually think it's obviously wrong. (It's uncomfortable for Democrats to oppose Trump doing the very things they championed under Obama, sure, but is it objectively any easier for him merely because Obama did it? I don't know.) I'd be interested to see a defence of (2), which seems to be the option most applicable to the UK.

Friday, 16 December 2016

Patriarchy is the Radical Notion that Men are People

Anne has a post arguing in favour of a libertarian feminism. It's well worth reading, not least because she's right. But as a persistent contrarian and well-meaning intellectual troll, I want to express some worries, hopefully mixed in with some encouragements, about the project.

To begin with a note of important agreement: libertarians should be more feminist, and should be open to revising their notion of coercion along feminist lines. The NAP is an insufficient framework for understanding oppression, and we should recognise that ideas can contribute towards material coercion even when they are just words. If we can recognise Marxism as a harmful ideology that oppressed the people of the Soviet Union, then we ought to be able to recognise the possibility that patriarchy is a harmful ideology that oppresses women.

Second, she is right that libertarians frequently ignore non-state sources of coercion. This is an accusation which can be made in a number of contexts - nostalgia for the clan systems which states displaced, private crime, etc - but which is not made often enough with regard to the household. The suffering of a citizen compelled to pay the wages of a social worker he will never need to access, while genuine and regrettable, is pretty trivial when compared to the suffering of a woman trapped with an abusive partner. Protesting the former situation while coldly observing that the woman is bearing the consequences of her foolish choice of partner makes it hard for libertarians to be taken seriously by anyone who gives compassion a role in their politics.

My main concern with the libertarian-feminism project is not that these ideologies are incompatible, but that their motivations might be. Libertarianism goes hand-in-hand with methodological individualism, the belief that the primary (perhaps only) actors in society are individual people. This is hardly surprising: if your political theory places great weight upon the choices of the sovereign individual, then you'd better be pretty sure that that individual exists.

By contrast, Marxists view the individual as insignificant when compared to the great movers of history: the economic classes. I'm not going to go into the details of this, not least because I don't know them. These are not the only ways of viewing the world - one might think human behaviour is best explained at the level of communities, of families, of genes, and probably many other levels besides - but they are both popular ways, and they are fundamentally incompatible. Hence individualists struggle to make sense of class conflict, while Marxists view all ideology as ultimately a cover for class interest.

Feminism, it seems to me, has a tendency to view the sexes in much the same way that Marxists view the economic classes. Men collectively oppress women in the same way that the bourgeoisie collectively oppress the proletariat. If Marxism is the attempt to understand the oppression of the proletariat and to unite them for the overthrow of the ruling class, feminism is the attempt to understand the oppression of the female sex and to unite women for the overthrow of men. (This is an exaggeration of most feminists' views, but there was indeed a strain in the 1970s, connected to the Wages for Housework campaign, arguing that the only way for women to escape male oppression is to disassociate from them entirely and adopt lesbianism en masse). They even suffer from the same inconvenience of having to explain why the state, which has hitherto acted only to promote the interests of capital/patriarchy, can suddenly be turned to the advantage of the working class/women.

It's hard for me to tell how far Anne subscribes to this view. For the most part she seems to endorse it: "The sort of radical feminism I’m interested in, and that I see as fitting quite well with libertarianism, sees that society is a patriarchy in which the class of ‘men’ oppress the class of ‘women’." At the same time, she observes that "Women are of course not uniformly oppressed or exclusively victims, and most definitely not a homogenous group with unitary concerns." Perhaps the tension between the positions is smaller than I think, perhaps she has a tension in her views. I don't know.

The picture of feminism I have presented is of course not the only vision of the movement. Intersectional feminism pays a great deal of attention to how different oppressions can interact, and (from my fairly cursory knowledge of feminism) seems like the kind of thing Anne might well be interested in. There are dangers with this view: firstly, that you end up in a kind of "Oppression Olympics" in which different minorities engage in interminable arguments over who has it worst. Secondly, one may ask in what sense this actually remains feminism, rather than merely a "coalition of the oppressed". Such a coalition is unstable, relying as it does upon nebulous judgements about what is oppression and what is merely misfortune (or indeed, self-inflicted harm). It also raises the question of why one cares about the things one does: if your aim is simply to make the world a better place, it seems highly unlikely that this is most effectively achieved by feminist activism. If your aim is to promote the interests of women, it seems equally unlikely that one will achieve this by allying with groups selected for being unsympathetic to mainstream society.

Once again, I don't wish to say that libertarianism and feminism are incompatible. Methodological individualism is compatible with all sorts of theories about why people behave the way they do, including a recognition of the power that ideas, whether or not they are consciously held, can have on society (ctrl-f "idealism"). Patriarchy may just be one such (harmful) idea. But the existence of such a tension may prove a barrier both for libertarians sympathetic to the oppression of women and for feminists leery of relying upon the state for their salvation.

To begin with a note of important agreement: libertarians should be more feminist, and should be open to revising their notion of coercion along feminist lines. The NAP is an insufficient framework for understanding oppression, and we should recognise that ideas can contribute towards material coercion even when they are just words. If we can recognise Marxism as a harmful ideology that oppressed the people of the Soviet Union, then we ought to be able to recognise the possibility that patriarchy is a harmful ideology that oppresses women.

Second, she is right that libertarians frequently ignore non-state sources of coercion. This is an accusation which can be made in a number of contexts - nostalgia for the clan systems which states displaced, private crime, etc - but which is not made often enough with regard to the household. The suffering of a citizen compelled to pay the wages of a social worker he will never need to access, while genuine and regrettable, is pretty trivial when compared to the suffering of a woman trapped with an abusive partner. Protesting the former situation while coldly observing that the woman is bearing the consequences of her foolish choice of partner makes it hard for libertarians to be taken seriously by anyone who gives compassion a role in their politics.

My main concern with the libertarian-feminism project is not that these ideologies are incompatible, but that their motivations might be. Libertarianism goes hand-in-hand with methodological individualism, the belief that the primary (perhaps only) actors in society are individual people. This is hardly surprising: if your political theory places great weight upon the choices of the sovereign individual, then you'd better be pretty sure that that individual exists.

By contrast, Marxists view the individual as insignificant when compared to the great movers of history: the economic classes. I'm not going to go into the details of this, not least because I don't know them. These are not the only ways of viewing the world - one might think human behaviour is best explained at the level of communities, of families, of genes, and probably many other levels besides - but they are both popular ways, and they are fundamentally incompatible. Hence individualists struggle to make sense of class conflict, while Marxists view all ideology as ultimately a cover for class interest.

Feminism, it seems to me, has a tendency to view the sexes in much the same way that Marxists view the economic classes. Men collectively oppress women in the same way that the bourgeoisie collectively oppress the proletariat. If Marxism is the attempt to understand the oppression of the proletariat and to unite them for the overthrow of the ruling class, feminism is the attempt to understand the oppression of the female sex and to unite women for the overthrow of men. (This is an exaggeration of most feminists' views, but there was indeed a strain in the 1970s, connected to the Wages for Housework campaign, arguing that the only way for women to escape male oppression is to disassociate from them entirely and adopt lesbianism en masse). They even suffer from the same inconvenience of having to explain why the state, which has hitherto acted only to promote the interests of capital/patriarchy, can suddenly be turned to the advantage of the working class/women.

It's hard for me to tell how far Anne subscribes to this view. For the most part she seems to endorse it: "The sort of radical feminism I’m interested in, and that I see as fitting quite well with libertarianism, sees that society is a patriarchy in which the class of ‘men’ oppress the class of ‘women’." At the same time, she observes that "Women are of course not uniformly oppressed or exclusively victims, and most definitely not a homogenous group with unitary concerns." Perhaps the tension between the positions is smaller than I think, perhaps she has a tension in her views. I don't know.

The picture of feminism I have presented is of course not the only vision of the movement. Intersectional feminism pays a great deal of attention to how different oppressions can interact, and (from my fairly cursory knowledge of feminism) seems like the kind of thing Anne might well be interested in. There are dangers with this view: firstly, that you end up in a kind of "Oppression Olympics" in which different minorities engage in interminable arguments over who has it worst. Secondly, one may ask in what sense this actually remains feminism, rather than merely a "coalition of the oppressed". Such a coalition is unstable, relying as it does upon nebulous judgements about what is oppression and what is merely misfortune (or indeed, self-inflicted harm). It also raises the question of why one cares about the things one does: if your aim is simply to make the world a better place, it seems highly unlikely that this is most effectively achieved by feminist activism. If your aim is to promote the interests of women, it seems equally unlikely that one will achieve this by allying with groups selected for being unsympathetic to mainstream society.

Once again, I don't wish to say that libertarianism and feminism are incompatible. Methodological individualism is compatible with all sorts of theories about why people behave the way they do, including a recognition of the power that ideas, whether or not they are consciously held, can have on society (ctrl-f "idealism"). Patriarchy may just be one such (harmful) idea. But the existence of such a tension may prove a barrier both for libertarians sympathetic to the oppression of women and for feminists leery of relying upon the state for their salvation.

Monday, 1 August 2016

Anything You Can Screw, I Can Screw Better

A party question for politically moderate Anglo-Saxons: which would be worse, Corbyn as Prime Minister with a substantial majority, or Trump as President?

I'm not going to answer that here. However, a couple of remarks:

(1) Prime Ministers are much more powerful than Presidents, due to the absence of checks and balances. Obama, a reasonable and essentially centrist President, has achieved virtually nothing since 2010 due to Republican majorities in Congress. Trump is a plain and simple fascist, so one would hope will face greater opposition.

(2) Trump is also known to have a very short attention span. The idea that he would have the endurance to push major law changes through is a dubious one.

(3) For that matter, Corbyn has proven consistently unable to even produce a policy platform. Imagine what he would be like if he not only had to think of policies, but put them into legalese and defend them against some former Oxford Union debating champion.

(4) Therefore, our fear of what Trump and Corbyn would be like should be rooted less in what we think either of them would do, but rather in what they wouldn't do. (e.g. defend the Baltic Republics/Falkland Islands).

(5) This fact, combined with Trump and Corbyn being the least qualified candidates for governing their respective countries since at least 1900 and 1983 respectively, ought to raise a few questions for libertarians.

I'm not going to answer that here. However, a couple of remarks:

(1) Prime Ministers are much more powerful than Presidents, due to the absence of checks and balances. Obama, a reasonable and essentially centrist President, has achieved virtually nothing since 2010 due to Republican majorities in Congress. Trump is a plain and simple fascist, so one would hope will face greater opposition.

(2) Trump is also known to have a very short attention span. The idea that he would have the endurance to push major law changes through is a dubious one.

(3) For that matter, Corbyn has proven consistently unable to even produce a policy platform. Imagine what he would be like if he not only had to think of policies, but put them into legalese and defend them against some former Oxford Union debating champion.

(4) Therefore, our fear of what Trump and Corbyn would be like should be rooted less in what we think either of them would do, but rather in what they wouldn't do. (e.g. defend the Baltic Republics/Falkland Islands).

(5) This fact, combined with Trump and Corbyn being the least qualified candidates for governing their respective countries since at least 1900 and 1983 respectively, ought to raise a few questions for libertarians.

Saturday, 23 April 2016

Does Liberalism Require a Free Market?

There has recently appeared on Facebook what is still provisionally called the Young Liberals Society. It's a group of mostly students who advocate free speech and so far seems to be little more than a discussion forum combined with a coordinating post for anti-NUS activism. Within the group there has been talk of expanding it into something more, for which watch this space.

Part of increasing the scope of what the group covers is changing the way it describes itself. The group's current focus on student politics (or if you're feeling generous, opposition to student politics) reflects the fact that it emerged largely in response to what are seen as anti-democratic, authoritarian values which pervade the leadership of student unions. Since many people want it to be more than "just another student politics group" and instead a genuine base of advocacy for liberal enlightenment values, that requires a better picture of what we stand for as a group.

Some things are obvious. Free speech and religious tolerance are obviously crucial values. Other things are clearly things which the group takes no official position on - e.g. Brexit (an in-group poll was evenly split 25-25 with 8 votes for abstention) and the Monarchy (the members are overwhelmingly in favour of retaining a monarch as the UK head of state, with a poll going 49-12 with 5 abstentions). What about free markets?

There's a definite libertarian strain within the group. (This is how I was introduced to the group - someone I met at the ASI and IEA's Freedom Week added me to it). And the word "liberal" is in the name. So can we say that the group is pro-free market?

I would suggest probably not. Liberalism and the free market, I believe, go together very well but liberalism does not logically entail any kind of support for the free market. Historically, liberalism has tended to mean the combination of five ideas:

Part of increasing the scope of what the group covers is changing the way it describes itself. The group's current focus on student politics (or if you're feeling generous, opposition to student politics) reflects the fact that it emerged largely in response to what are seen as anti-democratic, authoritarian values which pervade the leadership of student unions. Since many people want it to be more than "just another student politics group" and instead a genuine base of advocacy for liberal enlightenment values, that requires a better picture of what we stand for as a group.

Some things are obvious. Free speech and religious tolerance are obviously crucial values. Other things are clearly things which the group takes no official position on - e.g. Brexit (an in-group poll was evenly split 25-25 with 8 votes for abstention) and the Monarchy (the members are overwhelmingly in favour of retaining a monarch as the UK head of state, with a poll going 49-12 with 5 abstentions). What about free markets?

There's a definite libertarian strain within the group. (This is how I was introduced to the group - someone I met at the ASI and IEA's Freedom Week added me to it). And the word "liberal" is in the name. So can we say that the group is pro-free market?

I would suggest probably not. Liberalism and the free market, I believe, go together very well but liberalism does not logically entail any kind of support for the free market. Historically, liberalism has tended to mean the combination of five ideas:

- Individualism: Ultimately, what matters morally speaking is the individual. To the extent that we value anything above or below the individual person, it is because these things promote individual wellbeing and autonomy. Contrast collectivist views (e.g. fascism).

- Voluntarism: Individuals are the best judges of what is best for them. Contrast paternalistic and theocratic views.

- Naturalism: There is an objective and knowable way that the world really is. Contrast post-modernism.

- Idealism: Ideas can change society. Contrast Marx, who thought that all aspects of society were determined by the level of economic development.

- Moralism: There are knowable moral truths. Contrast post-modernism, for lack of a better-known punching bag.

Naturalism has some relevance to the burgeoning trans-war, but not to the society directly. Idealism and Moralism are pre-supposed by almost any group which aims to effect political change. I think that what the society is really concerned with are individualism and voluntarism. Individualism entails a commitment to increasing individual wellbeing; voluntarism implies that the best way to do this is through the promotion of individual freedom.

What is freedom? Or rather, what is the understanding of freedom which, upon sincere reflection, we would conclude is morally valuable? This debate has been going on since Two Concepts of Liberty, a lecture given by Isaiah Berlin in 1958. I'm going to sketch some of the positions that have been taken. These are not necessarily clearly separate from one another.

- Pure negative liberty. Freedom consists in not being prevented from achieving one's aims by another agent.

- Moralised negative liberty. Freedom consists in not having one's rights violated by another agent.

- Crude individual positive liberty. Freedom consists in being able to do things that one wants to do.

- Moralised individual positive liberty. Freedom consists in being able to do that which is right.

- Collective liberty. Freedom consists in taking part in a group which makes collective decisions, binding upon the members.

Different accounts are more popular with different groups. Nozickian libertarianism is essentially reliant upon (2); (5) has been used by everyone from Fascists to democratic theorists; (4) probably represents the closest there is to a consensus in academic political philosophy, albeit with a heavy dose of subjectivism about what is right. Personally I'm a bit closer to (3) than to (4), but the differences here are very abstract and not worth going into.

Liberalism, I would suggest, is completely at odds with (5). One cannot believe that individuals are the only source of value in this universe, then claim that they somehow become most truly themselves through political community with other people. But beyond that, all of (1) to (4) are potentially reasonable understandings of what it means to be a liberal. Do these definitions of liberty imply support for the free market?

(1) certainly does. If one does not take the market to be inherently unjust, (2) does also. There are reasons why libertarians like the free market beyond its consequences.

(3) and (4) are not so clear, however. Once we move beyond the question of "Is the free market simply the natural consequence of people being able to do what they like with their possessions?" to "Is the free market an effective way of allowing individuals to achieve good lives?" there becomes a lot more room for reasonable disagreement. Someone who denies that the answer to the first question is "yes" is fundamentally misunderstanding something. Someone who thinks there are systematic problems with the free market as a way of achieving individual flourishing is in my view empirically wrong, but the view seems conceptually coherent.

Of course, you don't necessarily need to think that only one conception of liberty is important. You can mix-and-match as much as you like, although it becomes harder to tell a story of how they all fit into the picture of morality.

Given this, I think that liberalism and support for the free market go together very well. But there is room to favour positive liberty, distrust the free market on empirical grounds, and therefore be an anti-capitalist of some sort.

Wednesday, 6 April 2016

Notes on Prague and ESFLC 2016

Last month the 2016 European Students for Liberty Conference (ESFLC) was held in Prague. The weekend of the conference happened to be followed by two Hungarian national holidays, so it seemed an entirely natural time to pay a visit to the city.

I caught the overnight train from Keleti Station in Budapest, arriving in Prague at 6:30am on the Saturday. As the train sidled towards Prague station I had a dramatic view of the city, which was something like this (I was too slow to get a picture myself):

The other thing is that not everything is as elegant as these highlights. The Vltava - at least as it appeared that morning - was a dull river bounded by sheer concrete. One could hardly imagine travelling down it for leisure.

It should be noted that it was overcast, weather which does not portray the city ideally. Furthermore, I was short on sleep from having struggled to grab even twenty winks on the train as it stopped and started its way through Slovakia and the Czech Republic. So perhaps this was something of an unfair judgement.

I spent a fair while at the conference waiting for it to begin. Eventually there was a breakfast, and then I went to a session on Freedom in Education. The biggest problem with this session - aside from the seats, which were spring loaded and would snap back upwards with a crash to deafen the whole room - was that all of the speakers seemed to have different ideas of what was meant by "freedom in education". One speaker was a French academic who was frustrated with the way that the left dominates the academy, and so viewed this as being about changing the curriculum to include more of the ideas of freedom. Another was concerned with trying to achieve a free market in education, to wrest control of schools from the government. Yet another was promoting the idea that schools should allow greater freedom to their pupils in terms of what they do in school. None of these are misinterpretations of the phrase "freedom in education", but the diversity of interests meant that they had very little to say to each other and the session was little more than a group of people each putting forward an viewpoint that they happened to hold.

The next talk I went to was much more interesting: a defence of Marx. To be clear, this was an ex-Marxist who was playing devil's advocate, and it focused only upon Marx's theory of historical progression. That said, it was a useful session which filled in a couple of the gaps that existed in my understanding of Marxist theory.

After this, there was lunch. All meals at the conference were provided, with the cost being included in the ticket price. Unsurprisingly there were long queues waiting to be served food, and the vegetarian food ran out quickly. You'd have thought that of all people, libertarians would realise that central provision of food at below-market price inevitably leads to queues and starvation.

Immediately following lunch there was a keynote speech on the subject of noticing and responding to surveillance. I arrived a bit late, got a bad seat, and couldn't really hear it. In the mid-afternoon there were a range of activities. Ever the political philosophy nerd, I went to a discussion of the link between religion and politics. I can't say it was very high quality; that said, it was probably no worse than the average undergraduate seminar. Other events included a gun-shooting session, because this was a libertarian conference and if there's one thing we like more than freedom, it's making use of that freedom in ways that annoy people.

I have no idea what I did following this. In any case, for the final session of the day I went to a talk given by Edward Stringham presenting some of the stuff from his book on how markets can exist even in the absence of government courts and regulation. It was much more strident than his appearance on EconTalk.

At this point there were a couple of hours going spare, so I went to the Easter Market in the Old Town Square. There was some traditional music and dance being performed, which made me nostalgic for the weekends I used to spend at IVFDF.

In the evening there was a thing going on at a club which had the enviable location of being in the middle of the Vltava. There was a good band playing live, we each got a free drink, and I had a couple of interesting conversations - one with a couple of guys from the other end of the Czech Republic, and one with Edward Stringham and with a girl from the Faroe Islands.

On Sunday morning, there was once again breakfast and I was able to have a conversation (along with three or four other students) with Bob Murphy. I can confirm that his unhealthy obsession with Paul Krugman is as present in real life as it is on the internet.

The first session I went to was one on the ancient Brehon law of Ireland, back in the days before England imposed a state on them. The talk was given by one Kevin Flanagan Coombes, whom you may guess from the name was himself Irish. Indeed half the talk seemed to be talking about how much the Irish were known for their love of justice. That said, there were some fascinating claims that I'd love to see made in a medium that people are more inclined to trust. These ranged from facts about the law (e.g. if a stranger arrived in an area, you were legally required to provide hospitality. This facilitated trade, and explains why the Irish are so friendly: because they would have been punished if they weren't) to its applications (e.g. apparently many tribes across the world who lack a written record of their laws have essentially adopted Brehon law, as they have judged it to be sufficiently similar to their own law to be indistinguishable). If half of these are true, it would greatly affect the way we think about law. Unfortunately, based upon some of his rather murky exegesis of the philosophy of law, I am not convinced that Mr. Flanagan Coombes is the best person to draw out these implications.

I didn't go to a second session, since none of them looked interesting. Instead I got my Kindle and read for a bit. Finally, the conference was closed by a talk given by Tom Palmer on students who had achieved great things for liberty. I didn't really real comfortable in the talk, it seemed very self-congratulatory to listen to a man talk about how we were all awesome and could change the world.

After scrounging as much as I could from what was left over from breakfast, I set out to make the most of the portion of the day which was left. Having not especially enjoyed the first day-and-a-half of my stay, I was determined not to waste the remaining two days.

There wasn't really time to go very far, so I had a look around the Jewish museum. The main museum wasn't very big, and the most interesting exhibit was a touchscreen which told the history of Jews in various places across Bohemia. The numbers of Jewish families seemed to be very variable, presumably due to the perpetual threat of Pogroms.

The museum closed before I had a chance to visit any of the synagogues, although fortunately the ticket was good for several days. Instead I went to have a look at the Powder Tower.

The next day I woke up bright and early in order to see Prague Castle. The weather had picked up very pleasantly, and on my way past the Astronomical Clock (I was staying at a hostel perhaps 100m away from it - the Prague Square Hostel, highly recommended) I was able to get this snap:

I took more photos on the way. This one should both show the grandeur of the castle, and the grimness of the river:

I spent the morning going round the castle. I don't have many photos due to the camera policies in there, but most of it wasn't especially visually interesting. There were some interesting stories - a defenestrated minister here, an enterprising artillery company there - but the bits I remember most strongly are the basilica and the Golden Lane.

In the afternoon I wasted a lot of time trying to visit an exhibition of the national gallery, forgetting that it was closed. With the second half of the afternoon I went around the Spanish Synagogue, a joyous explosion of colour that, had my 23andme results arrived sooner, would have made me proud of my (miniscule) Jewish ancestry.

I caught the overnight train from Keleti Station in Budapest, arriving in Prague at 6:30am on the Saturday. As the train sidled towards Prague station I had a dramatic view of the city, which was something like this (I was too slow to get a picture myself):

My first thought was, "Wow, this is really beautiful." My second was, "Wow, it's dirty." Making my way to the conference via the scenic route, I saw a fair bit to confirm my initial impression. There are beautifully painted buildings of the sort that you simply do not see in Budapest - but there seems to be far less pride taken in it. The shops on the ground floors of grand facades make no attempt to blend in, and there's graffiti everywhere (including on the Czech parliament building!).

The other thing is that not everything is as elegant as these highlights. The Vltava - at least as it appeared that morning - was a dull river bounded by sheer concrete. One could hardly imagine travelling down it for leisure.

It should be noted that it was overcast, weather which does not portray the city ideally. Furthermore, I was short on sleep from having struggled to grab even twenty winks on the train as it stopped and started its way through Slovakia and the Czech Republic. So perhaps this was something of an unfair judgement.

|

| A typically well-decorated building, ruined by the shops on the ground floor. |

The next talk I went to was much more interesting: a defence of Marx. To be clear, this was an ex-Marxist who was playing devil's advocate, and it focused only upon Marx's theory of historical progression. That said, it was a useful session which filled in a couple of the gaps that existed in my understanding of Marxist theory.

After this, there was lunch. All meals at the conference were provided, with the cost being included in the ticket price. Unsurprisingly there were long queues waiting to be served food, and the vegetarian food ran out quickly. You'd have thought that of all people, libertarians would realise that central provision of food at below-market price inevitably leads to queues and starvation.

Immediately following lunch there was a keynote speech on the subject of noticing and responding to surveillance. I arrived a bit late, got a bad seat, and couldn't really hear it. In the mid-afternoon there were a range of activities. Ever the political philosophy nerd, I went to a discussion of the link between religion and politics. I can't say it was very high quality; that said, it was probably no worse than the average undergraduate seminar. Other events included a gun-shooting session, because this was a libertarian conference and if there's one thing we like more than freedom, it's making use of that freedom in ways that annoy people.

I have no idea what I did following this. In any case, for the final session of the day I went to a talk given by Edward Stringham presenting some of the stuff from his book on how markets can exist even in the absence of government courts and regulation. It was much more strident than his appearance on EconTalk.

At this point there were a couple of hours going spare, so I went to the Easter Market in the Old Town Square. There was some traditional music and dance being performed, which made me nostalgic for the weekends I used to spend at IVFDF.

In the evening there was a thing going on at a club which had the enviable location of being in the middle of the Vltava. There was a good band playing live, we each got a free drink, and I had a couple of interesting conversations - one with a couple of guys from the other end of the Czech Republic, and one with Edward Stringham and with a girl from the Faroe Islands.

On Sunday morning, there was once again breakfast and I was able to have a conversation (along with three or four other students) with Bob Murphy. I can confirm that his unhealthy obsession with Paul Krugman is as present in real life as it is on the internet.

The first session I went to was one on the ancient Brehon law of Ireland, back in the days before England imposed a state on them. The talk was given by one Kevin Flanagan Coombes, whom you may guess from the name was himself Irish. Indeed half the talk seemed to be talking about how much the Irish were known for their love of justice. That said, there were some fascinating claims that I'd love to see made in a medium that people are more inclined to trust. These ranged from facts about the law (e.g. if a stranger arrived in an area, you were legally required to provide hospitality. This facilitated trade, and explains why the Irish are so friendly: because they would have been punished if they weren't) to its applications (e.g. apparently many tribes across the world who lack a written record of their laws have essentially adopted Brehon law, as they have judged it to be sufficiently similar to their own law to be indistinguishable). If half of these are true, it would greatly affect the way we think about law. Unfortunately, based upon some of his rather murky exegesis of the philosophy of law, I am not convinced that Mr. Flanagan Coombes is the best person to draw out these implications.

I didn't go to a second session, since none of them looked interesting. Instead I got my Kindle and read for a bit. Finally, the conference was closed by a talk given by Tom Palmer on students who had achieved great things for liberty. I didn't really real comfortable in the talk, it seemed very self-congratulatory to listen to a man talk about how we were all awesome and could change the world.

After scrounging as much as I could from what was left over from breakfast, I set out to make the most of the portion of the day which was left. Having not especially enjoyed the first day-and-a-half of my stay, I was determined not to waste the remaining two days.

There wasn't really time to go very far, so I had a look around the Jewish museum. The main museum wasn't very big, and the most interesting exhibit was a touchscreen which told the history of Jews in various places across Bohemia. The numbers of Jewish families seemed to be very variable, presumably due to the perpetual threat of Pogroms.

The museum closed before I had a chance to visit any of the synagogues, although fortunately the ticket was good for several days. Instead I went to have a look at the Powder Tower.

The next day I woke up bright and early in order to see Prague Castle. The weather had picked up very pleasantly, and on my way past the Astronomical Clock (I was staying at a hostel perhaps 100m away from it - the Prague Square Hostel, highly recommended) I was able to get this snap:

I took more photos on the way. This one should both show the grandeur of the castle, and the grimness of the river:

I spent the morning going round the castle. I don't have many photos due to the camera policies in there, but most of it wasn't especially visually interesting. There were some interesting stories - a defenestrated minister here, an enterprising artillery company there - but the bits I remember most strongly are the basilica and the Golden Lane.

|

| Pictures of the basilica. |

|

| Pictures of Prague from the castle. |

In the evening I went to a concert given in one of the churches by an organist and a small string orchestra. Hearing Bach on a proper organ is always a delight, and it was almost enough to let me forget how overpriced it was (at least compared to what I'm used to). Indeed, Prague in general is ridiculously expensive - more pricey than Manchester, more than twice as expensive as Budapest.

This was my final evening in Prague, which meant that it was a good time to visit the Prague Beer Museum. It's called a museum but it's really a pub with an unusually wide range of beers. Nevertheless, I was able to get a set of five contrasting beers, in small glasses of 150ml each.

|

| #SquadGoals |

To be honest I wasn't massively keen on most of them. A couple were somewhat experimental beers that didn't quite work out, but that's fine. Another was a bitter that, given a few years, I am sure I will mature into. The one I did enjoy was the one at the end, which was very light and a welcome relief from the previous beers, which had got steadily heavier.

After another good night's sleep, I made my way to the Kafka Museum. On the way I walked across the Charles Bridge, which remains a highlight of the journey. That's one thing which Budapest simply has no equivalent to. I have photos, but because I forgot my camera and instead used my phone they're potato quality:

Outside the museum was a somewhat obscene statue of two men urinating into the Czech Republic. Perhaps it was artistic; it was definitely crude. Their waists were moving from side to side, so that the streams of water were constantly moving.

Photos were prohibited within the actual museum. All I can say is that it gave a very good impression of the twisted, dystopian aesthetic of which Kafka was perhaps the greatest promulgator, and that I cam away knowing rather more of Kafka than I did when I went in.

After picking up my bags from the hostel, I went to the Antonin Dvorak museum. This is a modest museum, set in a single small building not far from the train station. It was by far the best value thing I did while there, at 30Kr (about £1) for entry.

After this I made my way to the train station and caught a train back to Budapest. Overall I'm happy to have gone to Prague, but will be quite happy if I never go again. If you want to experience the Central European aesthetic then there are far cheaper places to do so; Prague is arguably most exquisite than Budapest, though, and is undoubtedly far more walkable.

If you want to go to a Central European city for a stag weekend, please go to Prague and not Budapest. (a) It has better nightlife, and (b) you've already ruined bits of Prague. Please don't bring Budapest down to that level of tackiness.

If you want to go to a Central European city for a stag weekend, please go to Prague and not Budapest. (a) It has better nightlife, and (b) you've already ruined bits of Prague. Please don't bring Budapest down to that level of tackiness.

Sunday, 31 January 2016

What Should We Learn from Wilt Chamberlain?

Robert Nozick's Anarchy, State and Utopia is full of thought experiments which have become classics. Though the libertarianism which is central to the book has been less influential than the left-liberalism of his then-Harvard-colleague John Rawls, it is hard to name much - if anything - from Rawls' magnum opus A Theory of Justice which has been reused outside of a Rawlsian context. Nozick, however, has furnished us with The Experience Machine, The Utility Monster, and a whole host of ideas besides.

The idea which I intend to discuss is not one which has been, to the best of my (admittedly very limited) knowledge, outside of a libertarian context, but which I shall show has strong implications for how even those who disdain libertarianism ought to think about distributive justice. This idea, known as The Wilt Chamberlain example, comes from as passage entitled "How Liberty Upsets Patterns" and runs as follows. Suppose you have a society which enjoys perfect distributive justice. This might be perfect equality, it might be in exact accordance with some measure of desert - you name it. Nozick's argument is intended to be perfectly general.

Now Wilt Chamberlain, the legendary basketball player, is willing in his spare time to play basketball for the entertainment of other people; a million other people, in turn, are each willing to pay him $1 for the privilege of watching him. If these trades are allowed to happen then Wilt ends up vastly richer than other people in society. Hence either there can be no solid principle of distribute justice, or, in Nozick's words, "an egalitarian society would have to forbid capitalist acts between consenting adults". There's a bit more to it than that, but only in order to tighten up the details; the entire essence of the problem is contained in this paragraph.

This is a very persuasive argument. It's hard to argue against the freedom to make trades in which no-one is made worse off, but - suitably idealised - this is the whole process of modern capitalism. Must we accept libertarianism?

No, actually. There's a remarkably simple solution, which I'm amazed hasn't become the mainstream interpretation of where this argument ought to go. In a word: sufficientarianism.

Sufficientarianism is the view that equality per se is not what matters in terms of distributive justice; rather, we ought to care simply that each person has enough. What we mean by "enough" is a matter of some debate - it seems like every sufficientarian theorist has their own definition, none of which I am fully persuaded by. I won't pretend it has no difficultes, either - should we make the poverty of many people direr in order to bring a single person up to the line of sufficiency, as some formulations suggest? But it provides an easy, obvious answer to Nozick's argument. Our original stipulation was that everyone had enough. given that distributive justice had been achieved. Assuming no-one is putting himself below the line of sufficiency by buying basketball tickets, which seems to me a reasonable assumption, there is no reason why the distribution of resources should be objectionable after people have paid to see Wilt playing basketball.

We can have a view of distributive justice which does not hold it to be acceptable for people to be starving in the street, without having to interfere. Nozick's argument fails to establish libertarianism, but it functions as a strong piece of evidence in favour of sufficientarianism being superior to egalitarianism.

Wednesday, 27 January 2016

On "Integration" and the Current Migrant Crisis

I'm never quite certain whether, when people refer to integration of immigrants, they mean making those immigrants into full members of our civil society or whether they just mean persuading immigrants not to blow us up or sexually assault women. These correspond to two different views of potential immigrants: as people who look different but otherwise completely like us, or as the products of less advanced societies who hold correspondingly backward views.

The way many high liberals talk about the topic - as though integrating some migrants is the duty of a civilised society, but it is not something we need do with every single person who wants to enter the country - seems like it works far more with the second view of migrants. But these same people would be deeply uncomfortable with the implicit picture of migrants. Say what you like about Steve Sailer and such people: at least their view of immigrants is consistent with their politics.

Given that I'm on record as a supporter of open borders, it would be very convenient for me to hold the second vision of integration but the first view of migrants. This seems to be roughly what most open borders people believe, and with regard to your typical economic migrant I think it is probably the most reasonable view. But the "typical economic migrant" is selected for being relatively ambitious and cosmopolitan; the people fleeing Syria are simply trying to get away from a warzone, and do not appear to be selected for anything much other than being young and male. Obviously the pictures of migrants I presented at the start of this post are both exaggerations, and all actual migrants will fall somewhere between the two, but in general we might expect that the direr someone's circumstances are back in their country of origin, the closer they are likely to fall towards the uglier end of the spectrum. This is an uncomfortable fact for anyone trying to come up with a compassionate immigration policy.

This is rather unfortunate, and I don't really have a good answer to it. One option would be to take the deontological "immigration is a basic right which may never, under any circumstances, be denied" line, but I forfeited that principle long ago when I failed to apply it to Israel. Another option is to suggest that yes, there are costs to taking in immigrants, but ultimately we have to apply a sense of proportion: the benefits to the immigrants, most of whom are entirely law-abiding, vastly outweigh the costs to host societies. This is definitely the option to which I am most inclined, but it is not without its problems.

something which is distinctly more likely for them than for me - has nowhere else to go.

Second, there are the worries about cultural collapse. Social trust really is an important resource, even though I think conservatives tend to overestimate its volatility, and immigration really can harm it. Especially when the liberal authorities refuse to take genuine complaints about migrants seriously. Having read Haidt I do take this argument seriously, but what it really needs is to be put into quantitative terms. Social trust is, as with everything, the subject of a vast empirical literature, so how about we try to, however roughly, measure (a) the extent to which social capital is damaged by immigration, and (b) the extent to which other things we care about are damaged by loss of social capital? Perhaps we also place an inherent value on social capital, in which case that's also something to be factored into the equation.

In sum: I remain convinced that under normal circumstances, the UK ought to accept vastly more immigrants than it currently does. These are not normal circumstances, and I'm still trying to understand the implications of that. Deporting students - who are especially well-selected for liberal values, SJWs aside - is still stupid. But again, that's easy for me to say.

The way many high liberals talk about the topic - as though integrating some migrants is the duty of a civilised society, but it is not something we need do with every single person who wants to enter the country - seems like it works far more with the second view of migrants. But these same people would be deeply uncomfortable with the implicit picture of migrants. Say what you like about Steve Sailer and such people: at least their view of immigrants is consistent with their politics.

Given that I'm on record as a supporter of open borders, it would be very convenient for me to hold the second vision of integration but the first view of migrants. This seems to be roughly what most open borders people believe, and with regard to your typical economic migrant I think it is probably the most reasonable view. But the "typical economic migrant" is selected for being relatively ambitious and cosmopolitan; the people fleeing Syria are simply trying to get away from a warzone, and do not appear to be selected for anything much other than being young and male. Obviously the pictures of migrants I presented at the start of this post are both exaggerations, and all actual migrants will fall somewhere between the two, but in general we might expect that the direr someone's circumstances are back in their country of origin, the closer they are likely to fall towards the uglier end of the spectrum. This is an uncomfortable fact for anyone trying to come up with a compassionate immigration policy.

This is rather unfortunate, and I don't really have a good answer to it. One option would be to take the deontological "immigration is a basic right which may never, under any circumstances, be denied" line, but I forfeited that principle long ago when I failed to apply it to Israel. Another option is to suggest that yes, there are costs to taking in immigrants, but ultimately we have to apply a sense of proportion: the benefits to the immigrants, most of whom are entirely law-abiding, vastly outweigh the costs to host societies. This is definitely the option to which I am most inclined, but it is not without its problems.

something which is distinctly more likely for them than for me - has nowhere else to go.

Second, there are the worries about cultural collapse. Social trust really is an important resource, even though I think conservatives tend to overestimate its volatility, and immigration really can harm it. Especially when the liberal authorities refuse to take genuine complaints about migrants seriously. Having read Haidt I do take this argument seriously, but what it really needs is to be put into quantitative terms. Social trust is, as with everything, the subject of a vast empirical literature, so how about we try to, however roughly, measure (a) the extent to which social capital is damaged by immigration, and (b) the extent to which other things we care about are damaged by loss of social capital? Perhaps we also place an inherent value on social capital, in which case that's also something to be factored into the equation.

In sum: I remain convinced that under normal circumstances, the UK ought to accept vastly more immigrants than it currently does. These are not normal circumstances, and I'm still trying to understand the implications of that. Deporting students - who are especially well-selected for liberal values, SJWs aside - is still stupid. But again, that's easy for me to say.

Saturday, 31 October 2015

Against Libertarian Libertinism