But if there's no government, who will build the roads? This is apparently a question which genuinely gets asked, so I'm going to attempt to provide my answer here. [1] Or rather, I'm going to respond with a question of my own: why are roads different to the many other goods which we agree are best provided by the market?

Pictured: a list of things best provided by the free market.

One possible response for someone who hadn't really gone into the theory would be simply to suggest that a) roads are in practice provided almost universally by governments, and b) there is probably a good reason for this, hence c) we have reason to believe that roads are best provided by government. (It's true that there are private roads, but given that they are nearly all on private land I don't think this constitutes a real objection to the argument).

Just as I am wary of Austrian economics de to the general disregard of its adherents for empirical testing, I am wary of this kind of argument due to its lack of a theoretical explanation - one may as well label the proposed mechanism by which government intervention improves welfare as "magic happens". (This isn't intended as a strawman - it is better epistemic practice, when one is confused about a mechanism, to label it as "magic" than to dream up some believable but probably untrue explanation or to attach a meaningful-sounding buzzword which may convince you that you understand it). That said, this doesn't mean it is wrong.

There are two counterarguments which occur to me. The first is simply that there are many industries which are systematically dominated by the public sector when it is far from clear that this is a good thing - the best examples being currency, law and education. The second would be to note that the industries which are controlled by governments are often very important ones for the purpose of controlling a society. A society would be worse off for the loss of its pasta industry, but such a loss would be survivable; the same could not be said for currency, rights enforcement, or transportation. (Education - at least beyond a certain level - is probably not on the same level of importance as these, but let's not pretend that the primary reason for state intervention in education is anything other than a desire to indoctrinate children).

With that out of the way, let's look at the actual theoretical objections. The Wikipedia page on Free-Market Roads gives two objections: that roads are a natural monopoly, and that road privatisation would adversely affect the poor. I'll explain why I don't take either of these objections particularly seriously, why I might have taken the first one seriously a few decades ago, and I shall raise a (to my knowledge) completely original consideration which I suspect may provide a significant tendency towards less competition, but has only just occurred to me while writing this and I need to think about more.

Are Roads a Natural Monopoly?

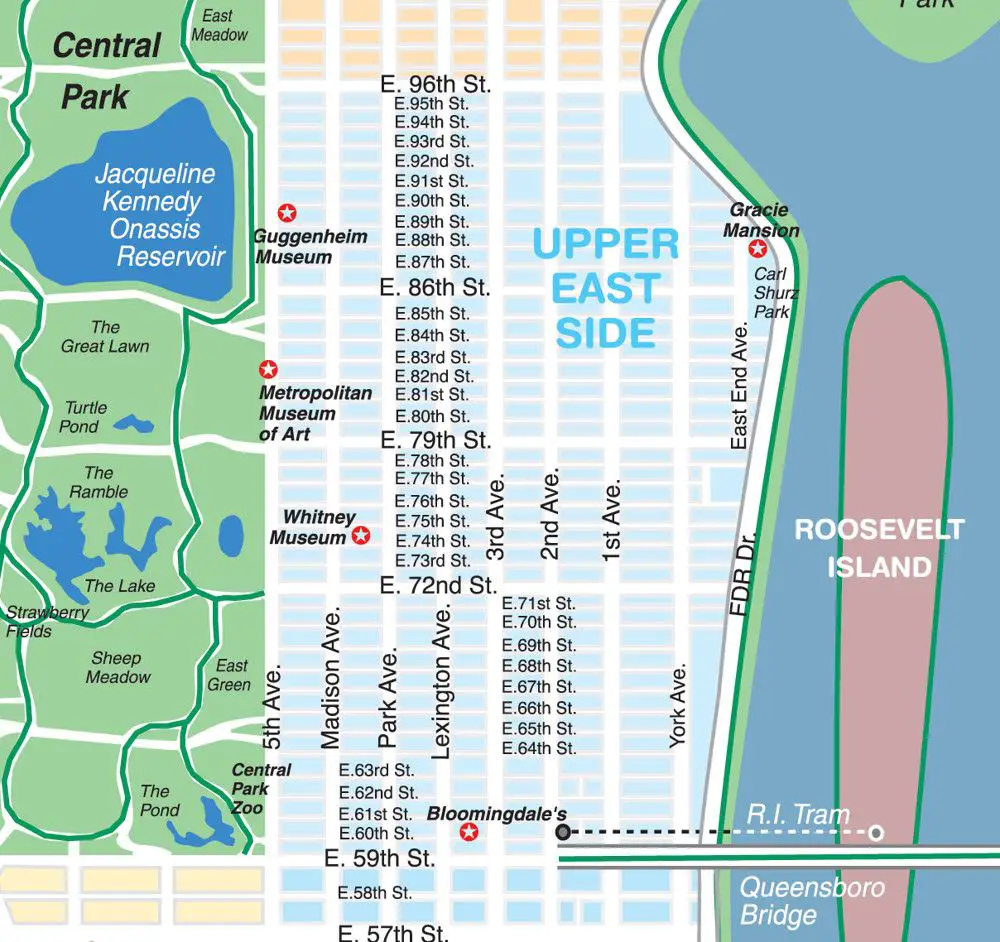

"In many parts of the world land use patterns mean that building two or more highways in parallel isn't practicable." Hence, the market cannot be contested and a monopoly arises. This is quite obviously nonsense, and to see why let's look at some of the most valuable land on earth: the Upper West and East Sides of New York City:

Do you see all of those roads in parallel? If they can get that many parallel roads on estate like that, I find it completely implausible that they can't do it pretty much anywhere else. After all, it's not like roads take up all that much space - if you turn a road into a tunnel you can always build on top of it. No, the idea that the roads cannot be built in parallel is rather silly.

It is true that there are significant costs to building a road so there may well be examples of local monopolies in formerly state-controlled areas with only one road. Suppose, however, that you were a private developer of houses or retail outlets. You would want to avoid large road fees nearby: retail and transport to retail outlets have joint demand, hence a rise in the price of one reduces demand for the other; similarly, houses and transport to/from those houses have joint demand. For this reason you would be keen to set up a competitive market for transportation to the places you were building.

A stronger argument would be that, rather than individual roads being examples of natural monopolies, networks of roads would be natural monopolies. It is not feasible to have a toll booth every time you move onto a new road, at least within an urban setting: having to show your card (or windscreen sticker) to someone at the end of every road would massively slow down your commute to work. Moreover, if one person doesn't have the relevant permission then this creates potential for a massive backlog which would hold up everyone behind him.

This would have been a good argument until the development of road cameras. In the modern state, these cameras are used primarily to catch people speeding; in Ancapistan, they would be used to check who was using a particular road so that they could be charged after the fact. There would of course be issues of people using someone else's number plate, but there's no reason why that problem should be any less rare in Ancapistan than it is in current societies. This would remove the need for people to stop or slow down excessively when moving between roads owned by different people.

This, my friends, is what freedom looks like.

There is still one possible issue: houses tend to be accessible to only one road, so we might expect these fees to be excessively high. The most likely answer is that residential roads would be owned by homeowner associations. These don't tend to exist in the UK and I've heard bad things about them from the US so I'm not entirely happy with this; all I can say is that monopolies cause deadweight loss, so if there is an alternative allocation of goods which leads to greater social welfare this will tend to be realised within the market - goods go to those who value them the most.

Would a free market in roads hurt the poor?

The description of this on Wikipedia is very vague. I'm not certain whether the objection is that markets cause poverty - in which case a) no they don't, and b) even if they did it would be far better to carry out redistribution purely in cash rather than through a single market - or that the tendency of pricing would be to make roads relatively more expensive for the poor.

I'll come back to that suggestion, but first let's think for a moment: how much would road access actually cost? I can think of four costs associated with people using roads: the cost of building them, the cost of maintenance, congestion caused for other road users, and the rent on the land taken up by a road.

The cost of building a road will affect market structure due to sunk costs, but since it does not affect the marginal cost of a road it will not affect the price of a road for a given market structure. As established above, we should expect the market for roads to be competitive.

The cost of building a road will affect market structure due to sunk costs, but since it does not affect the marginal cost of a road it will not affect the price of a road for a given market structure. As established above, we should expect the market for roads to be competitive.

The cost of maintenance cannot be all that big considering the amount a road gets used. This document is unhelpful, which is hardly surprising given its origin; this report gives Highways Agency maintenance spending as £663 million in 2014-15, which even assuming that government does it just as efficiently as private actors would, adds up to about £10 per person in the UK - perhaps £20 once we filter out non-drivers. Remember that this is an annual cost; hardly breaking the bank.

Of course, the government is known for the efficiency of its road maintenance.

What about congestion? I have no idea how to measure it, but my intuition is that it is pretty large relative to maintenance. Why? When you contribute to congestion for others, you also suffer it yourself. Suppose that by spending twenty minutes in a traffic jam, you slow down 120 other people's journey's down by ten seconds; in that case, you will inflict congestion equal to that which you suffer. If anything, I would expect you to slow down a greater number of people by a similar amount of time, in which case it only takes two hours of being in a traffic jam in a year to make this exceed your share of road maintenance cost.

Finally, rent. This is again hard to measure, to a large extent because of the extensive existing government intervention in housing and land causing the relative prices to be all out of whack. Furthermore, it's difficult to know exactly where roads would be built (affecting the cost of land) and whether they would be turned into tunnels (affecting the amount of land used).

Will any of these bias prices against the poor? The cost of road maintenance shouldn't, since that is determined to a large extent by weather patterns; rent should work in their favour, since they would a) tend to live in and therefore drive on cheaper land, and b) it would be more worthwhile for them to take a long-cut through cheaper land. The costs of congestion are largely non-monetary, but the biggest determinant of their value will be the value one places upon one's time - which will of course be smaller for poorer people. Hence, in a free market we should expect poorer people to face generally lower fees for road usage than rich people. This is because ultimately they are buying a different product - they are paying for access to a different set of roads, and so just as one pays less for a lower-quality car, a poor person in Ancapistan would face a lower charge to use the roads than a wealthier person.

A new consideration

A new consideration

Roads aren't just roads. The land underneath them tends to contain various pipelines and cables, because it's far easier to dig up a road than a house. It seems likely that in Ancapistan, ownership of the pipelines would be divorced from ownership of the roads above. But the owners of these will obviously have to interact - you can't just dig up someone's road whenever you need to.

"What's this about? Well, I just felt like digging up a road of a

Sunday afternoon. Not bothering you, am I?"

Sunday afternoon. Not bothering you, am I?"

Furthermore, I would expect there to be a substantial difference between the average length of pipeline owned by a single firm and the average length of road owned by a single firm. If a firm owns all the pipeline between (say) the water treatment plant or reservoir on one end and people homes on the other, this will most likely go under a considerable number of roads.

I need to sleep before I think all the way through the implications of this, but it seems like there could be problems resulting from this. Suppose the existence of a pipeline from location A to location B would create value for pipeline builder Dana of £x. There are n road-owners, each of whom has the power to veto the pipeline. Dana must reach an agreement with every individual road-owner for them not to veto the project, and it seems like a sensible solution might be for Dana to pay each of them £(x/n). But suppose one of them decides to insist on receiving £((x/n)+y), where y > 0. Then it would be in the collective interest of the other road owners to reduce the amount they charge Dana by £y, but it would not be in the interest of any individual firm. Moreover, if one firm can raise its price and other firms will reduce their prices to match, then it is in the interest of every firm to raise its price and the pipeline will not be built because poor Dana has no way of making a profit.

I don't think a social expectation of not charging for pipelines to go under your road is in the least bit likely, since there are very real costs to their prescence. Tying ownership of pipes to the roads only creates the same problem in a slight disguise - you have a value £x being somehow split between homeowner Dan and his water-supplier, with n pipeline-section-owners having an ability to veto the pipeline.

Note that this problem disappears if n equals one: the road owner charges £x and the pipeline gets built. If there is only one possible route by which the pipeline could go and n is large (with "large" defined as "too many for them to effectively coordinate and impose discipline upon each other"), then it seems like it will not be built. If there are multiple routes then this improves the chances of one of them not having a large value of n, but note that essentially there is a significant tendency towards monopoly in that this gives the best chance of this water (or sewage, or whatever) pipeline being built.

This may be a more fundamental objection that the standard "roads must be a monopoly" arguments, since they rely upon ignoring the fact that roads must compete with trains, footpaths, cyclepaths and other forms of transportation, whereas this objection, having nothing to do with their use for transportation, evades those sources of competition.

If you don't have a pipeline to take away the sewage,

you end up with a house completely full of shit!

Conclusion

I have no doubt that roads could exist in an anarcho-capitalist society. However, I have serious concerns regarding their interaction with other utilities, which may lead to a monopoly situation and hence inefficiency. I have not put nearly enough thought into this to conclude that there is no solution, but I do not have a solution ready to hand either.

The author of this essay wishes to thank David D. Friedman for making generally available his paper "A Theory of the Size and Shape of Nations"; much of the thinking in this essay was influenced by his discussion of the effect of trade routes on state revenue.

No comments:

Post a Comment